At 3 a.m. we tumbled into our bed in Squamish, after flying to Vancouver from New York City. The plan was to sleep in, but all I could dream about was the nearby Chief, a 2,200-foot-high granite dome in British Columbia with some of North America’s best climbing. By 9 a.m. I was drinking coffee in our hostel’s backyard while staring up at The Chief, drooling.

“Let’s climb The Chief today?” I said to Jenna.

It was no ordinary question. Jenna was four months pregnant.

For the last two months I’d been saying how excited I was to climb in Squamish, and she’d been saying how apprehensive she was about climbing a big wall while in her second trimester. Flashback two months…

Me: “I really want to climb The Chief,” I said, holding open the guidebook Squamish Select to show Jenna a trad route called Banana Peel, which had a difficulty of 5.7 with a protection rating of PG-13 (meaning there would be some runout sections). “I think this is well within your ability.”

Jenna: “Umm, I’ll be four months pregnant and I don’t know how I’ll be feeling.”

Me: “Beth Rodden climbed until she was six months pregnant.” (A professional climber, Rodden and her now-ex-husband Tommy Caldwell made the second-ever free ascent of The Nose on Yosemite’s El Capitan.) “And Emily Forsberg was cross-country skiing at nine months pregnant.” (A professional ski-mountaineer, Forsberg and her husband Kilian Jornet race up and down mountains together.)

Jenna punched me in the face.

“Stop comparing me to professional athletes,” she said. “Every pregnancy is different.”

“OK, but don’t say ‘no’ to doing it because you’re not sure how you’ll feel,” I said. “Just see how you feel then?”

Flash forward to present… We both knew Squamish would be our last big vacation, as well as our last big climbing adventure together, before having a baby. We wanted to make the most of it — without damaging the fetus or causing Jenna to go into preterm labor 1,000 feet up one of the largest stone monoliths in the world.

The weather was perfect — sunny, no clouds — which wasn’t to be taken for granted, given we were in a temperate rainforest where on average it rained at least every other day in May.

“OK, I’ll do Banana Peel,” Jenna said as we sat outside the hostel, “but I won’t go all the way to the summit.” Banana Peel ascended an area known as The Apron, which went about one-third of the way up The Chief.

“Let’s go!” I said.

Banana Peel

An hour later, down the road at The Chief’s parking lot, a climber saw me craning my neck to try to discern Banana Peel amid the sea of rock above us.

“I just speed-climbed Banana Peel in about 30 minutes,” the guy said. “It’s super fun! You should start with a route called Rambles, which connects to the second pitch of Banana Peel. It’s rated 5.8.”

“That sounds great,” I said.

Jenna glared at me. “You’re already trying to make me climb something harder than what I agreed on?”

“It’s only a one-move 5.8,” I said. “Let’s just check it out.”

Soon we were roping up at the base of Rambles. Jenna was unhappy.

“Why don’t you listen when I say I don’t want to do something?” she asked.

“Because I think you’re underestimating yourself and overestimating this climb,” I said.

The route began with a left-facing corner (5.7), no problem. Pitch 2 was a right-trending horizontal crack that led to a few 5.7 face moves, which Jenna easily dispatched again.

The third and final pitch of Rambles ended with a 5.8 pull over a roof. “You just climbed the hardest thing of the day,” I said to Jenna as she appeared over the lip.

“You sure that was 5.8?” she said. Compared to what we were used to climbing at the Gunks in New York, Rambles felt more like 5.6.

From the top of Rambles, we had the option of walking left in the brush to connect to Banana Peel, or going straight up the 5.10b slab of the route One Scoop with Delicious Dimples. Three bolts led to a tree.

“Might as well try it since we’re here, right?” I said.

I led, and then Jenna followed up the 5.10b slab without slipping once.

“You’re the slab queen!” I yelled to her. “I think you climb better when pregnant!”

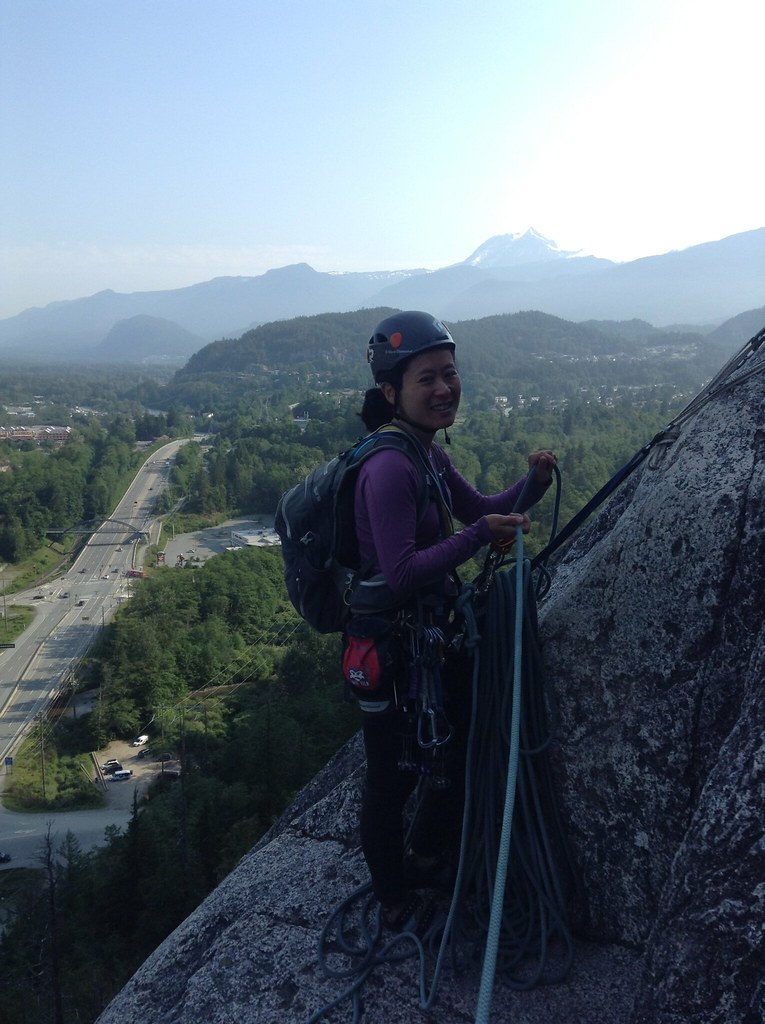

Now on pitch two of Banana Peel, which had a long rightward traverse, we were several hundred feet above the ground. Mount Garibaldi (elev. 8,786 feet) loomed in the distance.

Pitch 3 got interesting, requiring us to climb a few feet up a tree and then stem gingerly onto the slabby rock face, which had neither handholds nor protection for about 40 feet to another tree belay.

Pitch 4 was considered the crux of the climb, with a 40-foot runout to a bolt, and then another runout to a right-facing corner. Just as I was chalking up my hands to go up with all my gear, a ropeless climber appeared out of nowhere and waltzed alone up the slab. He was free-soloing in sneakers.

Wearing grippy climbing shoes, I nervously tip-toed up the same section. It may have only been rated 5.7, but the lack of protection was unnerving. Worst-case scenarios ran through my mind. If I slipped, I would tumble at least 60 feet, my body grating over the rock and jerking Jenna hard—if not ripping her down with me. I began to wonder if this was the best route to climb with a fetus on belay.

Pitch 5 was a mellow 5.4 up a groove to a notch where I built an anchor in the crack—almost all other anchors on this route were made from slinging a tree. Pitch 6 stepped onto the slab and wandered unprotected diagonally right for about 30 feet before reaching a bolt. It then ascended some flakes to a tree ledge, where Jenna took a power nap.

Jenna was cruising up the slabs. It was almost like the extra weight in her belly was lowering her center of gravity to provide better balance and foot purchase. She was so surprised with the ease of climbing that, after we finished the last two 5.4 pitches of Banana Peel at 3 p.m., I was almost able to convince her to continue climbing another 1,500 feet to the summit. The sun wouldn’t set until 9 p.m., giving us plenty of daylight.

“Nah, I’m hungry,” Jenna said.

I already had the guidebook open to look for more climbing routes. “The easiest route to the summit of The Chief isn’t harder than 5.9,” I said. “You know you can do it, because you just climbed 5.10.”

Her focus was on the onion rings.

We hiked down to the parking lot and were at the fast food restaurant A&W by 5 p.m. We thought we’d get a root beer float at A&W, but suddenly the entire menu looked amazing. The float came in a frosted glass mug and the root beer refills were unlimited. The juicy burgers were made from Beyond Meat. The sweet potato fries came in a fancy metal basket. Sometimes everything seems better in a foreign country.

Diedre

Days later we were back at the base of The Chief, this time to climb Diedre (5.8), which connected to Broomstick Crack (5.7), which connected to Squamish Buttress (5.10 or 5.9) to the summit. It was 7 a.m. A couple in their 60s was already roping up to climb another route; they directed us toward Diedre’s starting point. (I’m continually amazed that even the most famous climbing routes in Squamish or Yosemite, which have been climbed hundreds of thousands of times, remain unmarked and without any signs or trail markers—a remnant of the wilderness ethos of climbing.)

“Diedre is a classic, enjoy it!” the older man said.

As with Banana Peel, the hardest part about Diedre was the mental crux of unprotected slabs. And again, my pregnant climbing partner dispatched them easily. On the second pitch, instead of making a 5.6-rated 20-foot leftward traverse, Jenna upped the ante by climbing a few extra feet higher and then traversing leftward over a steeper section of slab.

“Are you trying to make the climb harder?” I shouted to her. “I think you just did a 5.10 variation!”

Pitches 3 and 4 were 300 feet of excellent laybacking up a right-facing corner. As I climbed, we both suddenly heard a “swoosh!” overhead. We looked up and saw someone parachuting from the top of The Chief. It was a BASE jumper. Another person came hurtling down in a wingsuit, soaring out over the ground before pulling the parachute.

Diedre’s final two pitches were 5.7 and a one-move 5.8 to exit into a forested area halfway up The Chief. We walked rightward about 20 feet to connect to the two-pitch Broomstick Crack (5.7), which had a beautiful, left-trending cleave in the granite. As we waited for a two-person party from Norway to get up Broomstick Crack, I asked what they intended to climb next.

“Not sure, we don’t have a guidebook,” the guy said. “Don’t we have to rap down after this?”

“You can climb all the way to the summit via the Squamish Buttress route,” I said. “Want to look at my guidebook?”

“I think we’ll do that, thanks!” the guy said.

At the top of Broomstick Crack, we untied and coiled the rope, then found a wind-sheltered spot to eat cheese sandwiches. It was another 30 minutes of hiking to the base of Squamish Buttress (in part because we accidentally passed the starting point and wandered so far right that the trail devolved into a narrow ledge alongside a 1,000-foot drop, at which point we realized we’d wandered into an area way beyond our ability and turned back).

Squamish Buttress started with several hundred feet of moderate 5.5. climbing with a few well-protected 5.8 or 5.7 moves. At pitch 4, we veered onto a variation called The Butt Light (aka The Butt Face), which is where things got fun.

The exposure ramped up as we stepped onto a 5.9 face above a deep gully. A few crimpy face moves led to a narrow, left-trending ledge.

Then came a 5.8 chimney with a funky top-out. We’d caught up with the Norwegian couple, as the guy was flailing inside the chimney.

“Want me to give you a tip?” I yelled to him. He nodded desperately.

“The guidebook says to keep your back to the wall,” I said.

The guy twisted around and now scooted easily up the chimney. Then his girlfriend followed. Now came our turn. I moved up about 30 feet and into the chimney, slipped a nut into the crack for protection, and yelled back to Jenna, “Bomber nut!” Famous last words.

As I pulled over the roof to exit the chimney, the nut popped out slid down the rope toward Jenna. I now faced a 60 foot fall. Frantically, I shoved a #4 camelot into the nearest crack.

Crisis averted, the climbing eased to mostly fifth class scrambling to another forested area, where we changed shoes and coiled the rope. The guidebook said that easy slabs led to the summit, but our route came to a final 5.6ish slab of 40 feet. I could hear voices of hikers on the summit. We changed back into our climbing shoes, tied back into the rope, and climbed the last bit to the tippy top.

Hikers gawked at us. “How’d you get here?” one asked. “How long did it take?” another asked. Then they looked at my pregnant climbing partner and said, “I guess it can’t be too hard.” Little did they know. I think Jenna’s belly had popped a few inches through the day.

It had taken about eight hours to climb to the summit. The 1.2-mile hike to the parking lot took about 60 minutes. Jenna has since gone pro.