Following on my first and second write-ups about Yosemite, here is the finale.

Chapter 6. Half Dome, Fully Done

The same morning that superstar climbers Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell were lacing up their La Sportivas in preparation for an unthinkable new speed record on the 3,000-foot-tall Nose of El Capitan, I was embarking on my own personal challenge halfway across Yosemite Valley: a second attempt on climbing Half Dome.

Jeff and I had failed to climb the iconic peak two days earlier, turning back after ascending 710 feet up the sheer northwest face. Maybe I needed that defeat to now go all-in on an alternate route up the southwest face: Snake Dike, 2,000-feet-long and rated 5.7 R. First climbed in 1965 by the flamboyant and reckless Jim Bridwell (who died earlier this year at age 73), Snake Dike is considered an all-time classic in Yosemite — with a big caveat in its “R” rating.

I usually wouldn’t climb something rated R. Modeled after the movie scale of G, PG, PG-13, R, and X, climbing routes are graded according to how protectable they are. G means there’s plenty of spots for gear, so you can protect yourself as much as you desire. X means there’s no protection, so you’re basically free-soloing like Alex Honnold. R means there’s minimal protection, so if you fall you’re going to fall far and it’s going to hurt.

But Snake Dike was my last ticket to Half Dome’s 8,839-foot-high summit. My way of convincing Jeff to climb something R was by promising I’d lead the scary pitches. Even then, anxiety had kept Jeff awake late as his mind turned over worst-case scenarios, which were made all the more real by three recent rescues on Half Dome and two deaths on El Capitan. And as another climber had warned us, if we fell on Snake Dike, we’d “roll down Half Dome like being ground over a cheese grater.”

We woke at 4am on June 6, embarking on the Half Dome Trail by 4:45am and finding the base of Snake Dike by 8am, 3,000 feet above the valley floor. We arrived just ahead of two other parties, which meant a small crowd looked on as I laced up my shoes. My backpack was a bit bulky with a Sugar Pine cone that I’d found along the trail. At 18-inches long, it was the biggest pine cone I’d ever seen. Carrying it up Half Dome seemed like a small burden for the reward of (fingers-crossed) bringing such an otherworldly token back home.

Pitch 1 began with the mandatory 80-foot-runout, followed by a 5.7 traverse across a 65-degree slab with no protection and no handholds. I waffled for 5-10 minutes, looking for the best spot to begin the traverse. Finally I stepped sideways and prayed my feet would stick. With each motion I was closer to a hold but in greater danger of a cheese-grater fall. Just as I felt a foot slipping, I reached up and grabbed the roof.

Jeff led the second pitch. Then I was up for the third, which Climbing magazine calls “possibly the mental crux of the climb, with an exposed 5.7 friction traverse.” It was indeed very mental. This was where our second summit attempt of Half Dome would either happen or not.

For another 5-10 minutes, I wandered up and down a 10-foot section of the cliff before finally stepping leftward and again praying my feet would stick. Thinking back, it was a wonderfully intense moment between me and Half Dome: my focus intense upon the granite, my eyes searching for any signs of a divot or nub for a foothold or handhold, my whole body and mind in the moment. It was also wonderful because I didn’t fall.

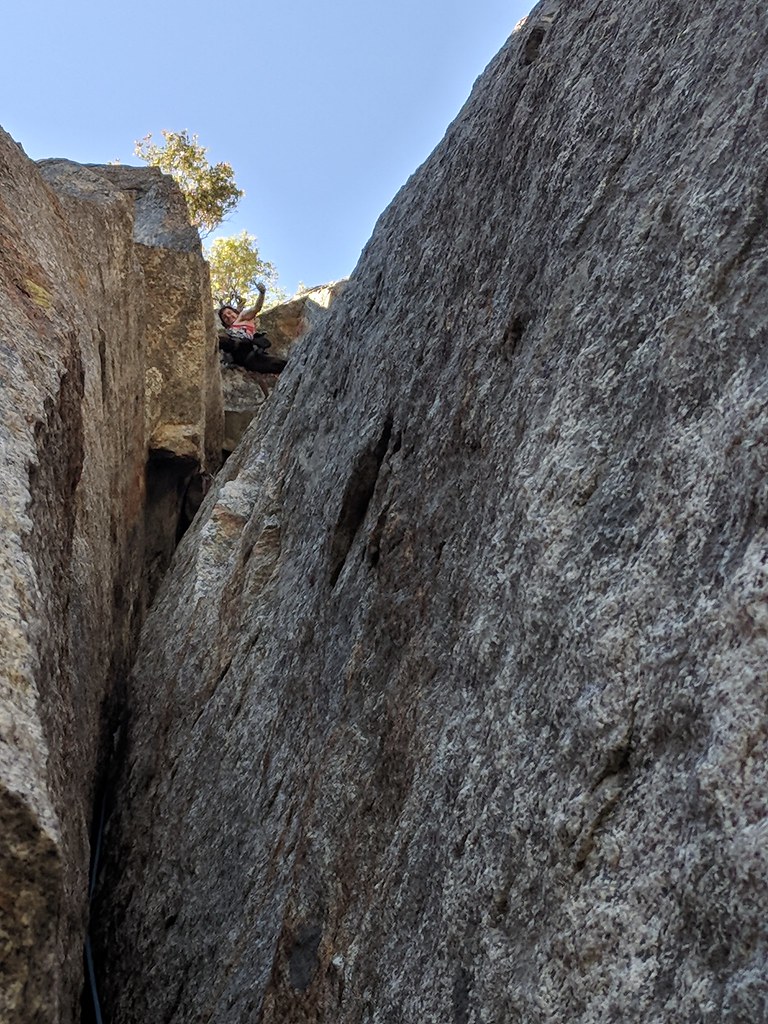

Above left, there’s no gear between the photographer (me) and the next person below (Jeff).

Above left, there’s no gear between the photographer (me) and the next person below (Jeff).

Then began a series of 60- to 80-foot-long runouts (meaning no protection) up the two-foot-wide, 500-foot-long dike. “It should really be called Dragon Dike,” Jeff noted.

I led the first runout, which was part of Pitch 3. Jeff, now feeling the excitement, led Pitch 4. I led Pitch 5, at the top of which I took the opportunity to relieve an aching bladder. It’d been four hours since I last peed and I couldn’t hold it any longer, even if we were 500 feet up the southwest face of Half Dome and several other climbing parties were following close behind.

Exposed to the world, I unzipped and let out a torrent on the granite. Ten seconds passed and I was still peeing.

“Dude, stop!” Jeff yelled. “It’s dripping on the rope!”

My pee was channeling down about 10 feet to where he was standing.

“Stop!” he cried. “You’re peeing on the rope!”

“Can’t hold it in,” I said.

“You have to stop peeing!”

We were almost up Half Dome and I wasn’t going to let an aching bladder stop me from continuing. Jeff would’ve been more livid, he later admitted, had he not also had to pee badly. He’d tried to pee but couldn’t under the pressure, and the pain in his bladder was essentially crippling him — meaning I’d be leading another pitch in a row.

As we were finishing Pitch 8, another climber came practically running up the face. He nodded at me, sat in the crevice of a ledge, and then, without placing a single piece of gear, yelled for his friend to start climbing.

“No pro?” I asked him.

“I’m good,” he said, or something to that effect.

In seconds, his friend (wearing rainbow-colored clown socks, and going by the name of Hobo Greg) sprinted up the cliff to where we stood and, without pausing, passed by his partner and continued up over another ledge. They used no gear for protection. If either fell, they’d both have likely tumbled all the way down Half Dome. Even if this final pitch was rated around 5.4 and the climbing was fairly easy, a fall could have meant a treacherous tumble. Jeff and I stayed on belay and moved cautiously.

From here, the climbing transitioned into low-angle scrambling for another 1,000 calf-burning feet to the summit.

A few cairns marked the way. In the distance we could see the snow-swept mountains above Tuolumne Meadows.

Then, finally, we were on the summit, posing for photos atop The Visor — an overhanging ledge that, two days earlier, we’d been standing far below when we first attempted to climb the northwest face. A dream two years in the making was complete: We’d climbed Half Dome, albeit not the way we expected.

It was a historic day in Yosemite for the greater climbing community. Looking down the valley, we could see the hooked brow of El Capitan, where Honnold and Caldwell had been that morning. Forty years ago, it was mind-blowing when the Nose was climbed in less than 24 hours by the late Jim Bridwell. Honnold and Caldwell had completed the 3,000-foot route in under 2 hours — something akin to running the mythical sub-2 hour marathon.

We relaxed for an hour with six other climbers who had come up Snake Route, an impromptu celebration of sorts. We also caught up with Hobo Greg, who, it turns out, has something of a reputation out West for his freewheeling lifestyle. Here’s his philosophy of life, as he wrote in The Climbing Zine:

Sure, in forty years, I may be greeting you at Walmart while you’re enjoying your retirement, but I’m retired now, when I’m thirty and can still do rad stuff, not when I’m seventy and am limited to bingo and ’bagos, only to have the latter surfed by dirtbags anyway.

You can imagine Hobo Greg has a fun Instagram page. Below left is a pic of him doing his crazy thing on the edge of the northwest face, and then me doing my tamer sit-down thing atop the Visor.

Marmot scurried between the summit rocks — how in the world did they climb to the summit? (And what did they name the route?)

Around 3:30pm, we began what felt like the most dangerous part of our time on Half Dome: descending the treacherous hiker cables.

Installed in 1919, the cables have been the scene of six deaths, the most recent on May 21 when a man slipped and fell. The granite here is smooth and slick from the boots of tens of thousands of tourists over the decades. The cables themselves are greasy and wobbly. Because I wore a harness I was able to clip into the cables for safety, but most hikers simply clung to the metal cables with their bare hands for dear life. I feared for them all.

Two-thirds of the way down the cables, I became stuck behind an 80-year-old man who was struggling to retreat on extremely wobbly legs. He’d made it halfway up, realized it was too dangerous for himself, and found another hiker to help him descend. It’s easy to imagine how, in a fast-moving thunderstorm, many people could become dangerously stranded here.

From the cables, we hiked down with a climber named Doug Dolginow, who had ascended Snake Dike with his son. He was a wealth of stories to help pass the miles…

Attending Harvard University back in the 60s, Dolginow was a member of the Harvard Mountaineering Club when it rebuilt its Harvard Cabin on Mt. Washington — which I’d directly benefited from, having spent many winter nights there. Dolginow later climbed with Yvon Chouinard and other legends in Yosemite before turning his focus to ski mountaineering and genetics. He’s since skied the world’s biggest mountains (including an attempt on Everest) and founded a number of genetic patents, including a technology to test for prostate cancer.

By the time we parted ways with Dolginow, we were more than halfway to the valley. Over the previous 72 hours, we’d hiked/climbed up 10,000 feet of elevation, and now we were in the final miles of descending those 10,000 feet of elevation. Jeff was so exhausted that I worried he might fall asleep mid-stride.

Chapter 7: My Kind of Cathedral

Driving through Yosemite Valley, you feel you’re in a kind of granite cathedral to nature. The soaring rock walls dwarf the grandest man-made temples like the Notre-Dame in Paris or St. Peter’s in Rome. It seemed fitting, then, that my final climbing day in Yosemite would be on a peak called Middle Cathedral (elev. 6,519 feet).

East Buttress of Middle Cathedral was first climbed in 1954 by the legendary Warren Harding, three years before his frenemy Royal Robbins became the first person to scale the northwest face of Half Dome. Not to be outdone, Harding one-upped Robbins by leading the first team up the Nose of El Capitan in 1958. It took them 45 days.

After we took a rest day following Snake Dike (which included some crack climbing on the fun 5.8/5.9 hand-and-finger Jam Crack), our final day in Yosemite began watching the rising sun hit the Dawn Wall of El Capitan.

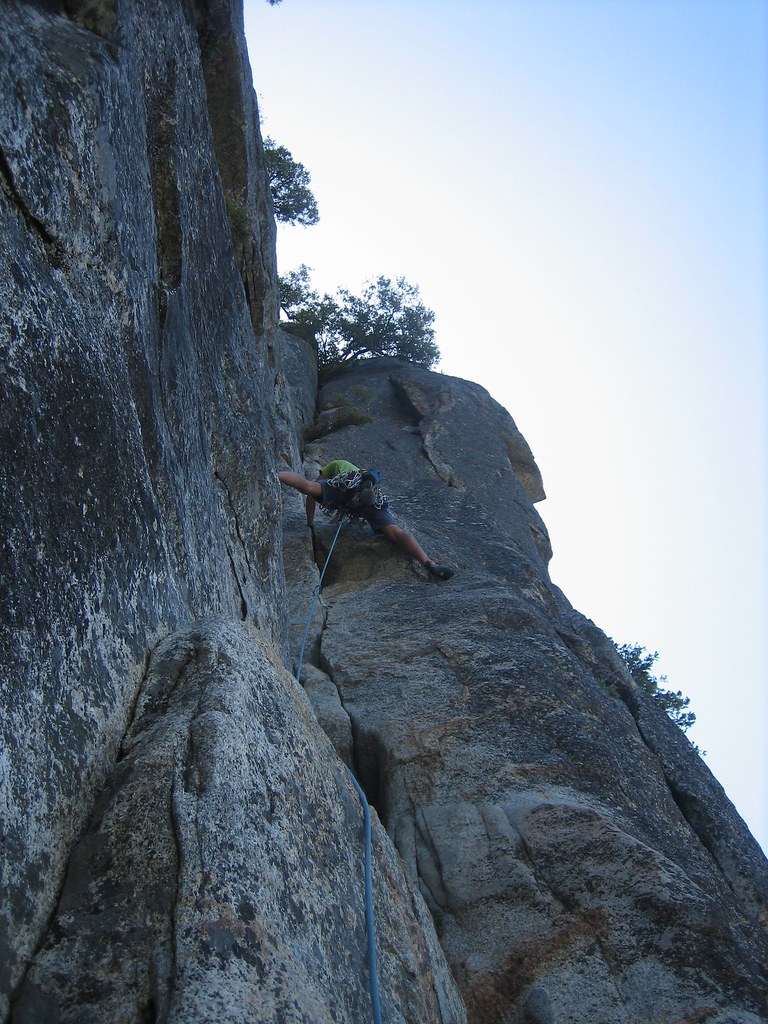

And then we began up Middle Cathedral. Mostly rated 5.6-5.8, but with several 5.9 roofs and one strenuous chimney, East Buttress (11 pitches, 1100 feet) is considered one of the top 10 climbs in Yosemite and one of the “Fifty Classic Climbs of North America.”

The terrain was fun and the exposure was thrilling…

The style of climbing was varied and the views were spectacular…

Even the harder 5.9 pitches felt notably “easier” than the 5.9 pitches we’d done on Half Dome. I kept thinking, “This is what Half Dome was supposed to be.” We’d come to Yosemite believing we could free-climb 5.9, been totally discouraged and demoralized when we couldn’t free 5.9 on the regular northwest face of Half Dome (albeit with 50lb weights on our bodies).

But now, here we were, freeing 5.9 in Yosemite. Was it just a different style of climbing? A subtle grading difference between a Warren Harding route and a Royal Robbins route? Was it the lighter pack load? Jeff and I would be parting ways the next day — him returning to live in the Middle East, me returning to a job in New York City — our paths diverging as sharply as they’d mysteriously crossed nearly two years earlier. But I couldn’t help daydreaming about another attempt on the northwest face of Half Dome…

After about 11 hours (including a very slow, bloody, and precarious chimney pitch), we were at the summit of Middle Cathedral. And as we found every day in Yosemite, we still had many hours before returning to the valley floor. This was our descent gully: