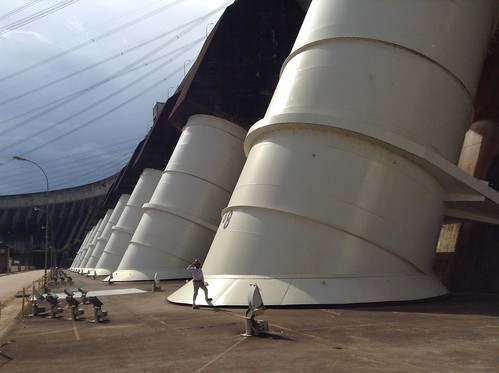

“It’s incredible,” I said, “I’ve never seen a bigger dam.”

“Neither have I,” replied the Brazilian chief of staff for Itaipu Dam, the world’s No. 1 energy-generating hydropower plant until a few weeks ago, when it was surpassed by China’s Three Gorges Dam.

Five miles wide, 65 stories tall, enough concrete to build 210 replicas of the 80,000-seat Maracanã soccer stadium in Rio de Janeiro, enough iron and steel to construct 380 Eiffel Towers… Itaipu Dam, completed in 1984 after a decade of construction on the border with Paraguay, is an impressive monument to Brazil’s old faith in hydropower.

But with Itaipu’s electricity production waning because of low river levels, and its No. 1 position lost to Three Gorges, this dam is also a glaring symbol of Brazil’s need to diversify its energy sources amid a major drought that is depleting hydropower reservoirs across the country and tipping Latin America’s largest nation into crisis, as I wrote for Americas Quarterly yesterday. Hydropower supplies three-fourths of the total electricity used in Brazil (compared to only 6 percent in the USA).

Earlier this month I visited the three-decade-old hydroelectric power plant, which is located not far from the famous Iguazu Falls, and met with chief of staff David Rodrigues Krug. Krug described his work at Itaipu as like chasing a unicorn: he wants to surpass 100 billion kilowatt hours of power generation in a single year (something that even Three Gorges hasn’t yet done), but he can never quite catch that number.

To give a sense of how much energy is 100 billion KWh: it’s 25 times as much electricity as produced every year at the Hoover Dam, and equivalent to the energy produced from burning 536,000 barrels of oil every day for a year at a thermoelectric plant. Visiting Itaipu, I could start to understand why it was named one of seven wonders of the modern world (along with the Panama Canal), and why the American composer Philip Glass wrote a 39-minute cantata to it.

Walking around the hydropower plant, amid the dwarfing proportions of the dam and the roar of water rushing through giant penstocks to 20 giant turbines deep underground, I couldn’t help but feel a kid-like wonder. Even the small details were fascinating, such as, in the elevator, the floors are labeled not by level but by elevation in meters above the sea.

At bottom is a video I took of one of the plant’s 20 turbines, which are each spinning out almost 1 percent of the total energy used in one year by the world’s fifth-most-populous nation! I could have touched the turbine. I could have sabotaged it, I thought. This answered my question as to why children under the age of 14 are not allowed inside the plant.

Throughout the tour I kept asking my guide, “What’s that do? And what’s that do? How fast is that spinning? Would I die if I jumped into the water here?”

Of course, plenty of people have died at Itaipu: 149 construction-related worker deaths, 80 spectators killed in a related bridge accident, 40,000 people displaced by the dam’s reservoir…

And then there’s the demise of the waterfall that used to be here, and the destruction of a natural habitat for untold number river and land species. Itaipu didn’t bother to create any type of fish-migration bypass until the past decade, though the fish-ladder was dry when I visited.

The 2014 documentary DamNation rattles through the many negative environmental impacts on US river systems from dams, many that weren’t even justified with a hydroelectric power plant, reminding me of the Fitchville Dam behind my childhood house in Connecticut, which was built in the 1800s to power a mill that burned down decades ago.

I think Itaipu can be justified by the energy it produces. The plant is projected to have a 200-year life span, which means another 170 years of operation… Of course, that’s assuming Brazil’s drought doesn’t continue drying up the rivers and hydro-reservoirs.